Buyer’s premium: is art becoming increasingly expensive?

[2021年03月09日]2013, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2019 … more or less substantial increases in buyer’s fees are regularly imposed on bidders.

The price reached when an auctioneer’s gavel drops – the hammer price – is not the price actually paid for the artwork. Auction houses take commissions, some of which are paid by the buyer who placed the winning bid. Since their systematic implementation in the 1970s, these additional costs have been constantly inflating.

Paul Cézanne, Montagne Sainte-Victoire, c.1885)

Take for example this superb Paul CÉZANNE (1839-1906) watercolour depicting the Sainte-Victoire mountain near Aix-en-Provence which sold for around $106,000 in June 2000. The auction house applied a buyer’s premium of 15% at the time, which therefore raised the price of the work to over $122,000. Nowadays, the same work – if sold at the same price – would cost the buyer around $133,000 ($11,000 more) as the buyer’s premium for this price range is generally fixed at 25%.

Buyer’s premium… how it works

Buyer’s premium (aka. auction fee or buyer’s fee) constitute the main source of income for the auction operator. They are used to finance a whole range of pre-sale preparations such as the creation of a catalogue, marketing costs, promotion via social networks… but also the personnel, the premises, the sales assistants and the computer equipment. They are therefore necessary for the smooth running of a sale. Other costs may be added to it, such as appraisal fees, transport and storage costs and, where applicable, fiscal charges and artist’s resale rights.

In short, each time a buyer places a successful bid, he/she or it (in the case of a museum for example) must pay an additional sum that is proportional to the hammer price. Auction operators are free to fix these fees as they wish, but when fixed, they are deemed non-negotiable. They vary from one auctioneer to another and according to the type of sale and are generally between 15% and 25% (excluding taxes) of the hammer price. The auction fees must be indicated in the sales conditions and publicly announced before the sale. It is therefore essential, before raising your hand, to remember that these amounts will be added if the bid is successful!

Nowadays auction operators are increasingly applying degressive sliding scale fees. For example, Phillips New York charges a 26% buyer’s premium for hammer prices between $1 and $600; 21% for successful bids between $600 and $6,000, and 14.5% for anything over $6,000. So… the higher the hammer price, the lower the fees. The major auction houses – present on several continents – fix their premiums in accordance with the different legislative frameworks applicable in each region. The amount of the buyer’s premium can therefore vary depending on whether the bid was made in New York, London or Hong Kong! This ‘flexibility’ has become increasingly complex as globalization has advanced and it has allowed a generally higher level of profitability for the auction houses.

Sometimes stable… but never decreasing, curves showing the evolution of buyer’s premiums have regularly edged upwards. In 1982, the New York Times reported that buyer’s fees at various international auction houses ranged from 8% to 16%. If one of them raises its fees, the others end up following suit. In 2017, the Journal des Arts captioned “Christie’s is again raising its buyer’s premium scale, after a similar initiative at Sotheby’s.” Two years later in 2019, the same newspaper posted almost the same title: “Following in the footsteps of Christie’s, Sotheby’s increases its buyer’s fees.”

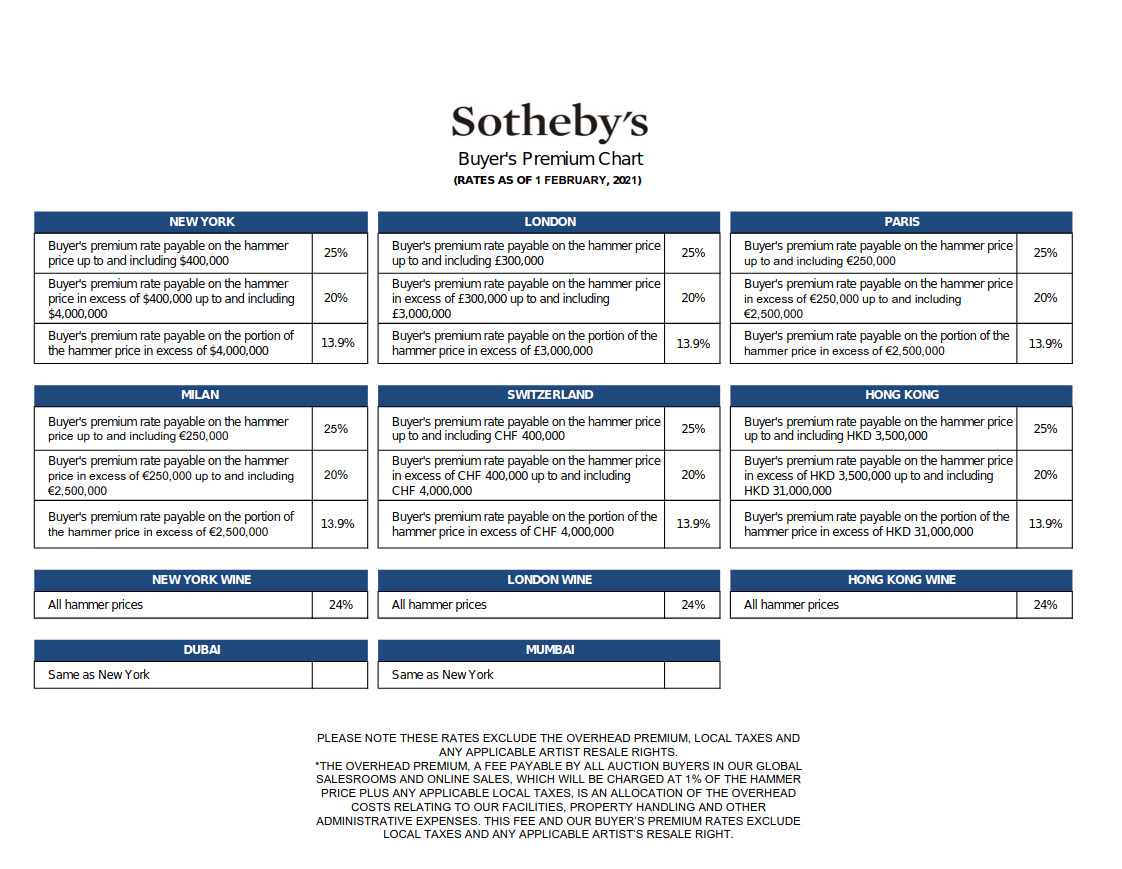

Since 2013, the buyer’s premiums on Fine Art sales have been raised no less than five times! For some art market observers, this indicates that the major auction houses, caught between attractiveness to sellers and profitability for buyers, are perpetually searching for a sustainable economic model. Just recently (since 1 August 2020) Sotheby’s created a surprise with a brand new “overhead premium” of 1% of the hammer price… on top of the buyer’s premium. This decision, apparently taken before the emergence of Covid-19, but implemented during the summer, will allow Sotheby’s to offset the negative financial impact of the pandemic and contribute towards the amounts already committed, for example, for the extension and renovation of its head office in New York.

Sotheby’s Buyer’s Premium scale, with the overhead premium’s addition in footnote

A little history …

Buyer’s premiums have not always existed; at least not in this form. Auctions were widely practiced in antiquity, especially in Rome and especially during the reign of Augustus. Before the existence of auctioneers, money traders served as financial intermediaries in transactions. They paid the seller the adjudicated price of the movable or immovable asset and then dealt with the buyer, to whom they granted payment terms and/or facilities for which they charged a commission ranging from 1% to 3% of the original amount made available. Today’s buyer’s premiums are ‘descendents’ of these charges.

A buyer’s premium of some sort has long been applied by auction houses throughout Europe, but in an informal and uneven way. The modern form as we know it today appeared much more recently (in 1975) in London at the initiative of Sotheby Parke Bernet (as it was then called) and Christie’s. This “creation” sparked a conflict that raged for nearly seven years. Three months apart, the two auction houses – already leaders on the art market – announced the establishment of a formalized payment system for buyers. The uncanny coincidence of timing sparked controversy as did the balance mechanism: by charging buyers a percentage of the hammer price, auction houses could reduce what they charged sellers, who previously bore the total cost of the sale, i.e. between +12% and +30%. The burden (and the risk) being reduced to between +2% and +10%, sellers were more likely to choose the auction route than that of selling through a gallery or an antique dealer…

The British Antiques Dealers Association and the Society of London Art Dealers went so far as to initiate legal action and the UK government launched an investigation under the UK’s restricted trade practices legislation (antitrust laws). It was not until 1981-1982 that a trial was avoided and the public inquiry closed. To resolve the dispute, the companies agreed to look at both the amount of fees charged to buyers and how they disclose the amounts paid by buyers. Over the years, auction houses around the world have followed the lead of Sotheby’s and Christie’s and have started charging buyers a fixed and automatic fee.

Online sales: the future

Additional costs may be incurred in the case of totally dematerialized “online only” sales (i.e. sales programmed for a specific period where bidding is via the Internet and there is no auctioneer). Indeed, some online auction platforms charge fees. In this case, the total amount to pay is calculated as follows:

The hammer price (for example $1,000)

+ the buyer’s fee (e.g. 25% of the hammer price… so $250)

+ internet costs (e.g. 3%… so $30)

= a total cost of $1,280.

Certain houses sometimes reduce buyer’s premiums for online sales, in order to offset the other specific fees. In September 2017, Sotheby’s took the art market by surprise by announcing the elimination of buyer fees on online sales! Internal research found that 45% of online shoppers were new customers, and best of all, 20% of those new customers had become traditional auction sales customers. Sotheby’s therefore wanted to consolidate this trend and double the number of sales made online only. However, seven months later, in April 2018, Sotheby’s announced the return of online buyer’s fees as their elimination had weakened the profitability of these sales. This illustrates the dependency of auction operators on commission-based income. In any case, whatever the format of the auction, we are unlikely to see a drop in buyer’s premiums anytime soon!

0

0