Focus on Yun Hyong-keun 윤형근 : Calligraphied matter

[2023年03月10日]“What is painting? I still don’t really know the answer. Is it a mere trace from combustion of life?” – Yun Hyong-keun, 1976

At the height of his fame in Korea and around the world, the young singer RM – leader of the K-Pop phenomenon known as BTS – recently released a solo album titled Indigo. A sort of thoughtful return to the thunderous beginnings of his career, the ten tracks and the album-cover reference a Korean artist with a very specific aesthetic called Hyong-Keun YUN (1928-2007) who seems to have played a mentor role – across generations – for the 28-year-old poet-rapper. The first track on the album bears the name of the painter and opens with a sound archive sample where Yun wonders about how to reach artistic truth. According to Park Kyung-mee, founder of the PKM Gallery and representative of Yun Hyong-keun’s beneficiaries, RM is very sensitive to the message of integrity and perseverance of the artist and is part of a generation which “feels very comfortable and confident about their inherited culture.”

Cover of RM’s solo album Indigo featuring Yun Hyong-keun’s artwork Blue

Trauma generation

Yet Yun Hyong-keun’s life seems a long way from the globalized and digital reality experienced by the young 21st century pop star. The decade between 20 and 30 years-old, which the BTS singer returns to in his album “Indigo”, was so traumatic for Yun that he spent the following decades trying to exorcize it from his mind. Yun Hyong-keun was born in Cheongju when Korea lived under inflexible and repressive Japanese domination, and his coming of age coincided with the end of Japanese colonization and the start of the Korean War (1950-1953) which was followed by unpopular American domination. In 1947, Yun enrolled in the Faculty of Fine Arts at Seoul National University (SNU) where he met Whan-Ki KIM, his mentor and later father-in-law. Strongly influenced by his master, Yun sought his own artistic vocabulary via large lyrical compositions in bright colors. While attending University, he opposed the military regime. In 1948 and 1949, he was arrested, tortured and expelled from the SNU for having taken part in student demonstrations. When war broke out in 1950, his subversive background played against him and he was once again detained, even narrowly escaping the firing squad. In 1956, Yun was again imprisoned for six months in the prison of Seodaemun. Transferred to another university, he finally graduated and taught in high school. He then began to exhibit his work in 1966 at the Press Center Gallery in Seoul, and then at the 10th São Paulo Art Biennial a few years later.

In the 1970s, Yun found himself in the crosshairs of the Korean Intelligence Agency for having exposed manifest corruption within the administration of his high school. On his release from prison, placed under surveillance, he was blacklisted and struggled to find a suitable job.

“Even though the period of youth during one’s twenties should be great, I spent mine living in a nightmare. Thus, the warm and beautiful colors disappeared from my works and were replaced with dark and heavy hues.”

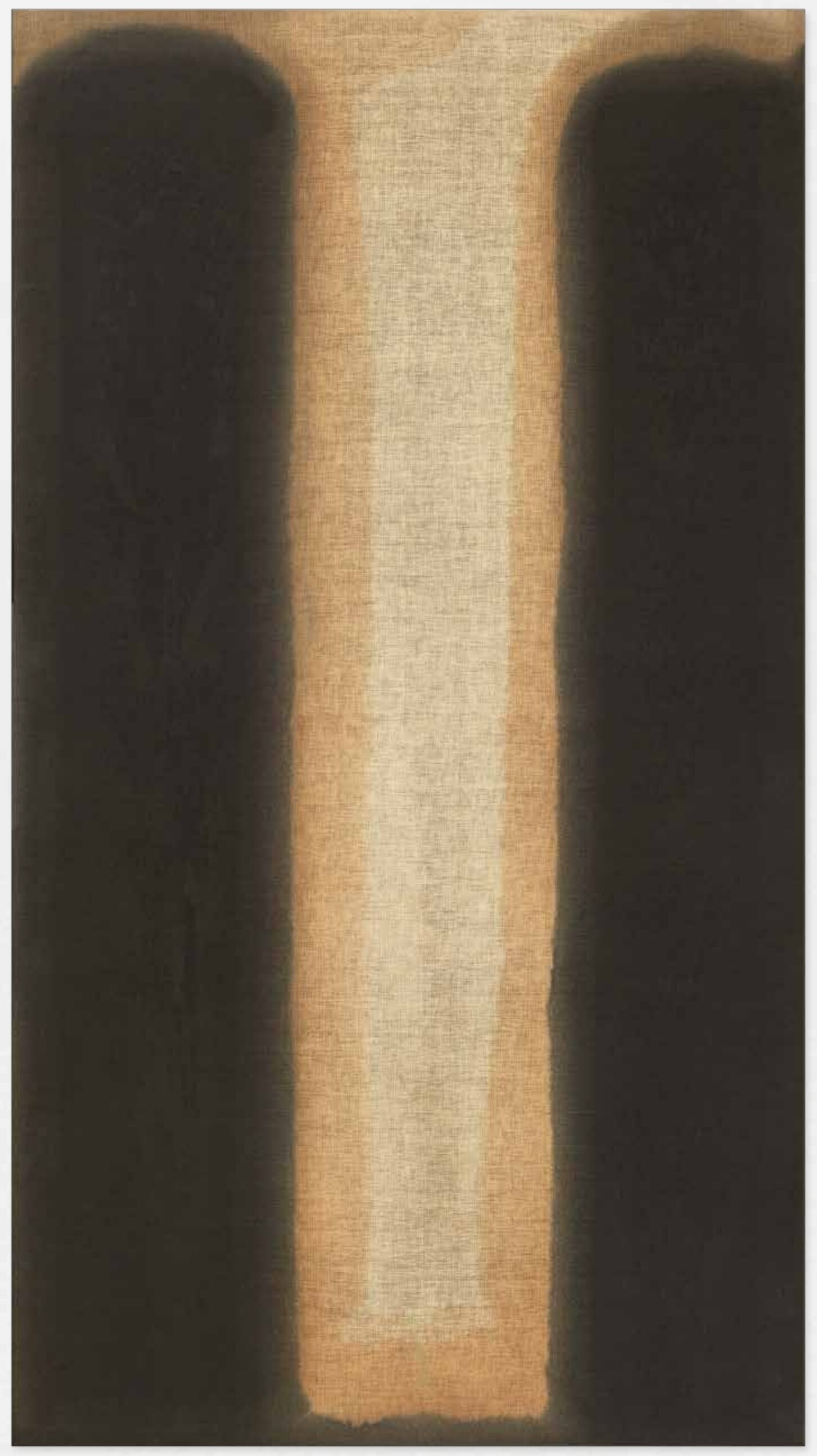

YUN, Hyong-Keun, “Umber-Blue 7-IIII-75”

Yun subsequently turned definitively to painting seeking – to the point of obsession – an answer to his suffering in a series of poignant meditations entitled “Burnt Umber and Ultramarine”. Strongly impressed by nature and the way the soil absorbs organic matter, Yun sought to capture the essence of this process by the way he worked the materials in his paintings. This resulted in a radical approach in which he limited his palette to dark earth tones, burnt umber and ultramarine, superimposing several layers of oil paints. These two colors represented earth and sky and the artist referred to his monumental works as “gateways to heaven and earth”. But he also developed a method of applying colors directly on raw cotton or unfinished linen, creating rectilinear pillars that appear almost black, and then thinning the paint with turpentine until it fused with the fabric unevenly, depending on the thickness of the layer and the points of the canvas. This allowed the colors to flow on their own, naturally, like water seeping into the ground. Works from this series have generated the majority of Yun’s public auction sales as well as his Top 10 auction results, including his auction record for “Umber-Blue 7-IIII-75”, a large painting from 1975 that sold at Christies HK in 2016, and whose updated value from Artprice confirms the excellent development.

No one is a prophet in his own country

Still blacklisted in his own country, Yun sought to exhibit his work abroad. He went to New York in 1974, where he came into contact with the work of post-war American artists like Mark ROTHKO and liked his way of dividing pictorial spaces. He also developed a friendship with Donald JUDD who was impressed by the physical presence of his work. Later, in the early 1990s, Yun exhibit in Judd’s spaces on Spring Street in New York and in Texas (Marfa).

In 1978 Yun was in Paris to show his work at the Second International Meetings of Contemporary Art at the Grand Palais. Two years later, deeply shaken by the Gwangju massacre of May 1980 in Korea, Yun and his family decided to move to France where he came into contact with other Korean artists like Sang-Hwa CHUNG, Guilin KIM and Tschang-Yeul KIM and settled into a studio where the 19th century French painter Camille Corot had also worked. As of 1980, his paintings became even more radical: black monochromes, with a low concentration of oil making them even more opaque. The pillars are no longer straight or vertical, but tended to sag, even collapse on top of each other, in a symbolism of dereliction. This Parisian period was the subject of an exhibition at the Zwirner gallery in February 2013 which notably highlighted his works on ‘hanji’, Korean paper, illustrating the meticulousness with which Yun chose his materials. According to the gallerist, Yun declared Hanji feels right for my paintings because, like cotton, it feels warm, simple, and it absorbs paint well… it is produced by hand, not by machine, it has a warmth and simplicity that makes it like a work of art.

YUN, Hyong-Keun, “Umber Blue ” 1985-86

In 1982, Yun Hyong-keun returned to Korea for good. His work finally began to be appreciated in Japan and in his native country. Today, thanks to Donald Judd and his American exhibitions, he is also well collected in the United States. But despite his decisive period in France, Yun’s work remains relatively unknown in Europe and his market recognition on the continent is much more recent. Jean Brolly, the first gallerist to have exhibited his work in 2002 and 2006, recalls the lack of commercial success he had back then. After Yun’s death in Seoul in 2007, the Korean gallery PKM took over the artist’s estate and along with Yun Seong-ryeol, his son, ensured the dissemination of his works, linking them to the movement Dansaekhwa and to its illustrious representatives such as Ufan LEE and Chang-Sup CHUNG.

Dansaekhwa 단색화 (One color, monochrome)

Dansaekhwa is the label used retroactively to characterize the work of of Korean artists as of around 1975. It was not an ‘official’ artistic movement as such and no manifesto has ever been written. However a number of artists, including Young-Woo KWON, Dong-Youb LEE and Seo-Bo PARK shared the similar ways of working and attached great importance to color, gesture and materials. They triturated their materials, flooded their canvases, brushed the colors and crumpled their papers. Their works reflect a search for purity and erasure. They engaged in an ascetic practice of repetition and monotony, similar to that of calligraphy, where the whole body is involved. Indeed, one could describe Dansaekhwa as the martial art of art, involving the total commitment of the artist. Abstract, but retaining legible formal elements, it is now the best-known vein of Contemporary Korean art in the global art world. In this Dansaekhwa constellation, Yun, an older artist, participated in the reflection around the artistic research of his contemporaries. Highly respected by his peers, he acted as a moral support, while fiercely maintaining his independence from any theories.

This is partly what explains the growth of the artist’s market, which is now tending towards the price levels reached by Lee Ufan and Park Seo-Bo, both still alive and active. Several major retrospectives have contributed to Yun’s recognition, notably that of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Seoul in 2018, which was transferred the following year to the Palazzo Fortuny in Venice. Meanwhile, the Korean art market has been expanding with its Fine Art auctions posting annual turnover growth in proceeds from sales of 310% between 2020 and 2022 and a number of major galleries have opened new branches in Seoul in recent years including Emmanuel Perrotin, Lehmann Maupin, Pace and Thaddaeus Ropac. Will David Zwirner be next?

0

0